The CPIM’s “tears” today for migrant workers therefore smacks of hyper hypocrisy. By destroying states in which they have ruled, by destroying local industries in states in which they have been in power, the CPIM has decimated support systems and has gradually turned entire generations into migrants.

During the election campaign for the West Bengal assembly in 2011, leading light of the CPIM, Housing Minister Gautam Deb, when asked why people have repeatedly voted the Left Front to power, replied with a flourish, that “The Left Front’s success” was “due to the heightened political consciousness of the people of Bengal, utterly devoid of material considerations.” The Left Front was completely routed in that election.

For 35 years the CPIM and its partners in the Left Front, had ensured that the people of West Bengal, whether they want it or not, remained perpetually devoid of any material advancement, opportunities or avenues. Violent and militant trade unionism led to the flight of capital, while party apparatchiks and big-wigs struck deals to keep themselves afloat and well supplied. This became the new normal in the state in the decades between 1977 to 2011. It continues to this day, albeit in an altered and restructured format.

The CPIM’s “tears” today for migrant workers therefore smacks of hyper hypocrisy. By destroying states in which they have ruled, by destroying local industries in states in which they have been in power, the CPIM has decimated support systems and has gradually turned entire generations into migrants. In the thirty-five years that it ruled West Bengal, the CPIM presided over one of the longest and most sustained periods of de-industrialisation and destruction of local industry and artisanal clusters that the state has seen.

Some argue that the Left Front inherited a crumbling industrial infrastructure, in that case, they miserably failed to put it back on track, in over thirty years of unbroken rule. Such a calculated callousness led to the impoverishment of the state and to the neglect of its rural hinterland. Let us take one example.

In 2007, the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSS) established that “nearly eleven percent families” in West Bengal, “faced starvation during several months of the years” which was “one of the highest among any states in India.” Starvation deaths among tribal families, such as the one that occurred in Amlasole in Midnapore, West, in 2004, was common and each time one saw, the CPIM pass it off as due to some disease. Even after 27 years of rule, the condition and availability of basic infrastructure in places like Amlasole, in 2004, was shocking. The “peoples’” government of the CPIM had only constructed one well for supplying water and the area had no health care facilities, except for a few roaming medical vans.

This is how committed the Left Front was to the empowerment and development of the tribal regions and districts of the state. In 2006 large scale starvation deaths occurred in the tea gardens of North Bengal with tribals and labourers of those gardens shut by the management bearing the brunt, but the CPIM government did little to mitigate the situation and continued being a denial mode.

In later years Mamata Banerjee’s dispensation did little to improve the situation and even late as 2019, a survey conducted by the Pratichi Institute and the Asiatic Society, found that there was food scarcity “in varying degrees” in 31 one percent of the tribal households in West Bengal. Towards the last part of CPIM rule, (1994-2005) to be precise, the agricultural sector too was destroyed by being neglected and by being allowed to be taken control of by party supported monopolies.

In an analysis of the wasted decade from around 1994 to 2005, veteran bureaucrat and policy analyst, sometime secretary rural development and executive director of the ADB in Manila, D. Bandyopadhyay, who had spearheaded the “Operation Barga” observed how, this falling apart of the agricultural sector was because of the Left Front government’s lack of endeavour to “push up agriculture production and growth” which was characterised by a low and next to no “investment in agriculture during” this phase. With the “extension services” totally collapsing and the market being operated by “predatory manipulators’” who denied the poor “farmers their [actual] rightful price”, the agricultural sector in West Bengal rapidly declined. The industrial sector had already taken a beating.

Bandyopadhyay also points out how, “The process of land reforms was halted. There was no regulation of any sort on the prices of inputs. Seeds had to be purchased in open market from big firms whose quality was not always certified and growth of rural wages also got stalled.” This led to the “diffusion of income in the countryside” being “restricted, causing distress, food insecurity, hunger, malnutrition, destitution and morbidity.”

The Communist politbureau now wails over the plight of migrant workers and attempts to deflect the narrative from how the party destroyed Bengal’s industry and agriculture, and forced lakhs to become roving workers in search of work and security. These market manipulators that have been referred to, were all controlled by the ruling CPIM.

Rural West Bengal’s life and its political and commercial transactions were mostly always controlled by armed gangs, colloquially called “Harmad Bahinis”, outsourced groups who would levy taxes, control the distribution and sale of agricultural produce and also keep the local party machinery well-oiled.” This same system has now been adopted by the Trinamool Congress, with local satraps calling the shots.

On coming to power in 1977, the CPIM, the largest constituent of the Left Front allotted the industry portfolio to its junior partner the Forward Bloc, allowing the sector to drift away. While industry suffered with a systematic de-industrialisation of the state picking pace, rural connectivity, infrastructure and healthcare were neglected. As opportunities dried up, with flight of capital began the shift of people and rural West Bengal began emptying up.

Only the party cadre and faithful was rewarded. The usual method was to fund local clubs which would keep an eye on the people of the area, report to the party’s LC (Local Committee) and also ensure that the syndicate kept in its control whatever minor business activities took place in the area. This whole parasitical system has now been taken over by Mamata Banerjee’s ruling TMC. One saw how during this period of the Corona pandemic and lockdown, her party and state machinery were busy distributing largess to its web of local clubs. The only permanent contribution of the CPIM to the economy of West Bengal has been the creation of this “infrastructure” of local clubs which were patronised by it. These, in turn, kept the party informed and supplied at the local level. In all these decades, the Congress was mostly in power at the Centre and it had a well calibrated partnership with the CPIM in West Bengal as well as in Delhi. It never rocked the boat, took the Left parties’ support whenever needed and always managed to bargain for itself a few seats from the state in Parliament and in the Assembly.

Throughout these years the Congress was equally complicit in the destruction of West Bengal’s industry and avenues of employment. The Congress never asked difficult questions, it did not launch any major political movements against the Left Front and made no determined and credible efforts to unseat the Communist regime and arrest the tide of West Bengal’s degeneration. The two parties worked hand in hand to destroy the state from its foundation and to impoverish its people.

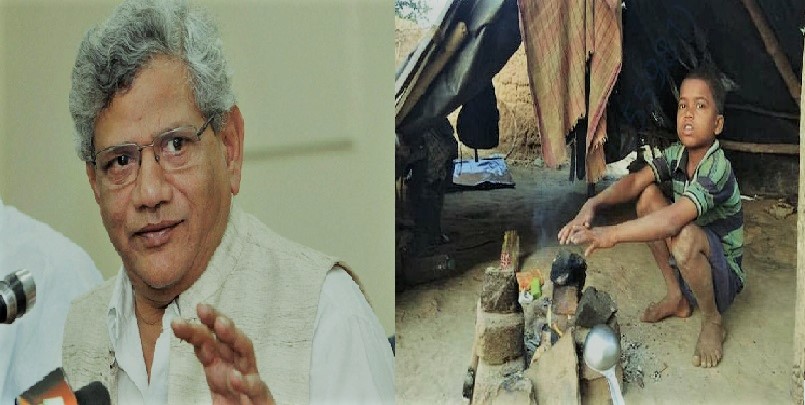

When one, therefore, sees Comrades Sitaram and his politbureau cohorts shed tears over migrant workers, when one sees, the brother-sister duo of the Congress party, mock migrant workers by resorting to sly utterances and cheap gimmickry, let us recall the plight of West Bengal’s past and its present. That tale and its truth exposes many a political grandstanding of the present.

Ref:

Abheek Barman, Left Rules West Bengal for 34 years and ruins, Economic Times, May 17, 2011

D.Bandyopadhyay, On Poverty, Food Inadequacy and Hunger in West Bengal, Mainstream Weekly, 19 June, 2007

(The writer is Director, Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation, New Delhi, views expressed are his own)