This is the other Tagore, which we have been taught to forget, but which we must persist in remembering. While being a globalist, this Tagore was firmly rooted to the soil of our cultural expressions. He rose to become one of its foremost voices. While remaining away from the bustle of public action, this Tagore had a clear vision of what he wished India to become, how wanted her education to be transformed, how he wished her history to be taught, how he aspired for her people to return to their roots. A few of his tracts are relevant in this context.

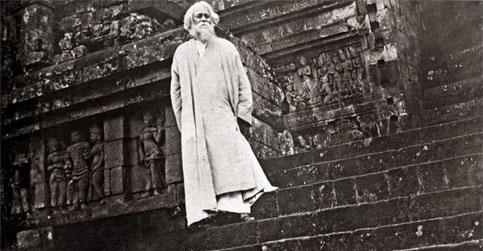

Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore, like a number of his illustrious contemporaries was richly multi-dimensional. Some dimensions of his personality have been emphasized, while others have been allowed to be conveniently marginalized. The left communist intellectual cartels had poured scorn on Tagore terming him a “bourgeois” poet, who only runs after or paints the joys of life, “anandabadi.” These communist pygmies had argued that Tagore lives in an ivory tower and is a poet of the skies. This assessment of theirs was in line with their political ideology of trying to “deconstruct” anyone who has contributed fundamentally to the shaping of our collective civilizational and national sense. Tagore was pre-eminent among such personalities.

Sometime after their drubbing in the assembly elections in 2011, former Chief Minister of West Bengal and communist leader Buddhadeb Bhattacharya admitted to their mistake in evaluating Tagore. Bhattacharya spoke of some “dwarf” intellectuals having made a mistake in their assessment of Tagore, “they could not understand him”, he had said. But it was a very easy way out. Indian communists have always resorted to such tactics, abuse our national icons, heap calumny on them, oppose and obstruct them in their lifetimes and decades later make a few amends and then begin appropriating them by presenting them in the same piecemeal manner in which they had been deconstructed. It is in seeing Tagore in completeness that we shall better contextualize and situate him in our quest for India’s civilizational repositioning.

This is the other Tagore, which we have been taught to forget, but which we must persist in remembering. While being a globalist, this Tagore was firmly rooted to the soil of our cultural expressions. He rose to become one of its foremost voices. While remaining away from the bustle of public action, this Tagore had a clear vision of what he wished India to become, how wanted her education to be transformed, how he wished her history to be taught, how he aspired for her people to return to their roots. A few of his tracts are relevant in this context.

In a seminal essay on India’s history – Bharatbarsher Itihas (1903), Tagore writes, that the “The history of India that we read and memorize for our examinations is really a nightmarish account of India. Some people arrive from somewhere and the pandemonium is let loose. And then it is a free-for-all: assault and counter-assault, blows and bloodletting. Father and son, brother and brother vie with each other for the throne. If one group condescends to leave, another group appears as if out of the blue; the Pathans and the Mughals, the Portuguese and the French and the English together have made this nightmare ever more complex.” But this was not the real history of India. Bharatvarsha could not be glimpsed through these surface narratives, “dreamlike scenes’ imposed by observers who studied Indian externally.” The truth was that “while the lands of the aliens existed, there also existed the indigenous country”:

Otherwise, in the midst of all the turbulence, who gave birth to the likes of Kabir, Nanak, Chaitanya, and Tukaram? It was not that only Delhi and Agra existed then, there were also Kasi and Navadvipa. The current of life that was flowing then in the real Bharatavarsha, the ripples of efforts rising there and the social changes that were taking place — none of these find an account in our history textbooks.

In his essay on “Swadeshi Samaj” (1904), another of those essays of his which is hardly discussed and dismissed as his “early” thoughts, Tagore spoke of possessing the country “through service and sacrifice.” A provocative piece in which Tagore calls for a returning to roots, Swadeshi Samaj, in his owns words, discussed “how to make my motherland my own” and that the country “must be saved – not from the hands of others – but from our own inaction and indifference.” Replete with brilliant and provocative passages, the essay needs greater reiteration and dissemination. “Know this – in India there has always existed a force to unify the whole country.

Even in the most unfavourable circumstances India has always made some arrangement; that is how it has been saved…Our country is building up a strange balance between the ancient and the new this very moment…” On the societal texture of India, Tagore argues, “To feel unity in diversity, to establish unity amidst variety – this is the underlying religion of India. India does not regard difference as hostility; she does not regard the other as enemy. That is why without sacrifice or destruction she wants to accommodate everybody within one great system…” But this meeting point, as Tagore calls it, “will not be non-Hindu, but very specifically Hindu…”

His Letters from Java – Java Jatrir Patra – letters that he wrote during his tour of Southeast Asia in 1927 are an immortal collection giving the reader a deep and wide insight into India’s civilizational footprints and her past cultural spread and space. The inveterate traveler, Tagore was one of the most enthusiastic and keen articulator of civilizational India. In these intricate islands, nations and people, replete with a rich historical and cultural tapestry he sought to re-discover the images and living linkages with civilizational Bharat, her Hindu past. As he wrote inspiringly:

The relics of the true history of India are outside India. For our history is the history of ideas, of how these, like ripe pods, burst themselves and were carried across the sea and developed into magnificent fruitfulness. Therefore, our history runs through the history of the civilization of Eastern Asia…The civilization of India like the banyan tree has spread its beneficent shade away from its own birth-place…India is not confined in the Geography of India – then we shall find out message from our past.

In his first letter from on board the Amboise, on way to Southeast Asia on his “pilgrimage”, as he referred to the trip, he movingly wrote of India’s contribution to the region, “the thought also strikes me that what India offered [to this region of southeast Asia] was not any dry preaching. What she gave roused inner wealth of man in all its aspects – architecture, sculpture, painting, music and literature. Its traces are to be found in deserts, in mountains, in far away islands, in inaccessible places as well as in soaring ideals.” While his letters from the Soviet Union have been discussed ad nauseam, his letters from the waters and the lands of Southeast Asia are more relevant in the present context of India’s rise and shall continue to remain dynamic. This is the other Tagore that needs rediscovery and contextualization. He will prove to be an invaluable guide in India’s current global emergence, as a pragmatic and sturdy power willing to expand and protect her interests.

Gurudev’s public stance after Swami Shraddhanand’s assassination in Delhi by a Tablighi adherent in 1926 was unapologetic. He castigated the Hindu samaj’s inability to unite in face of challenge, “the fact that we keep getting beaten up reflects our collective weakness, a state of weakness invites oppression and fear”, he had publicly lamented brimming with inconsolable grief. This other Tagore is extremely inconvenient for those who bound him into the “globalist” mould for the convenience of their narrative.

In a talk on the “The Centre of India Culture”, (1919), Tagore castigated the habit of dumping our past altogether, in the quest for modernity. He cautions, against trying to be “insularly modern.” There are some, he says:

who are insularly modern, who believe that the past is the bankrupt time, leaving no assets for us, but only a legacy of debts…The unfortunate people, who have lost the harvest of their past, have lost their present age…We must not imagine that we are one of these disinherited peoples of the world. The time has come for us to break open the treasure trove of our ancestors and use it for our commerce of life. Let us, with its help, make our future our own – never continue our existence as the eternal rag-picker at other people’s dustbins.

This is the other Tagore, who must continue to inspire us because he continues to be the nemesis of those who wish us to be a disinherited and deconstructed nation and people. These interpreters and self-styled legatees of Tagore’s oeuvres, work to dump and denigrate our civilisational achievements and have attempted to appropriate and condition Tagore to suit the contours of their false and violent ideology. This is what the Left in India did to him: first attack him, deconstruct his work of a lifetime, repudiate him and then when convenient appropriate and suppress him in parts.

It is that other Tagore therefore that we ought to rediscover, re-state, liberate and celebrate. It is in him that lay the seeds of India’s global rise, civilisational unfolding and collective rejuvenation.

(Bharatbarsher Itihas: translated from original by Prof Sibesh and Sumita Bhattacharya, the full essay is available at: http://www.ifih.org/TheHistoryofBharatavarsha.htm)

(The writer is Director, Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation, New Delhi, views expressed are his own)