Anirban Ganguly

The lighting of the Savarkar Jyoti at Cellular Jail will not only keep ignited the flame of freedom, it should also re-kindle a genuine  interest in this period of our independence struggle, an interest that may culminate in a grand memorial someday

interest in this period of our independence struggle, an interest that may culminate in a grand memorial someday

Life in a jail”, wrote Vinayak Damodar Savarkar from behind the iron-bondage of the dreaded Kala Pani, “for good, for evil, is a unique chance. Man can never go out of it exactly as he came in. He goes out far better or far worse. Either more angelic or fiendish. Fortunately for me, my mind has so quickly adapted itself to the changes in circumstances. It seems strange that a nature so restless and active, roaming over continents, should so quickly feel quite at home in a cell hardly a dozen feet in length. And yet one of the kindest gifts of Providence to Humanity is this plasticity, this adaptability of the human mind to the ever changing environments of life.” It was this stoicism, this unflinching oneness of purpose and this undiluted firmness of conviction that defined Veer Savarkar’s life’s actions and enabled him to pass through some of the most acute and excruciating incarcerations over a period of nearly four decades.

The confines of the Cellular Jail, also brought out the thinker and visionary in Savarkar. Not that the trait did not exist earlier, his insistence on terming the war of 1857 as the First War of Independence, his constant ruminations and intellectual churnings in the midst of planning revolutionary activities in London, displayed sparks of that deeper possibility. But it was through the intense suffering in the Cellular Jail — which could not daunt him — that emerged the epochal thinker and strategist. The condition of the Indian society, the need to strengthen and unify it, the future of that society and its continued existence through a process of cleansing that would lead to greater unity and cohesion was what occupied his thoughts.

On the question of caste, for example, he wrote after having read the novel Samaj Rahasya during his internment, “The greatest curse for India is the system of castes…It must be swept away, root and branch, the best means to that effect is a crusade against it, in all forms of literature, especially drama and novel. Every true patriot should cease to have double dealing and speak out his mind clearly and act up to it…” Of course communist historians with Stalinist mindsets, sponsored and tamed by the Nehruvian establishment, had no use for such utterances, they had set their eyes on painting Savarkar’s legacy and thoughts in black in their quest to portray nationalists and those articulating the Hindu view as fascists and feudalists — it served the aims of their political patrons who wanted to shove down the national psyche, a unilateral narrative by marginalising some of India’s best minds.

It was Savarkar’s unalloyed nationalism, intense patriotism and a burning desire to see India free that sustained him through the most difficult phases during India’s struggle for freedom and the same intense attachment to the motherland, expressed, for example, in a sentence he wrote from Kala Pani, “in your answer please inform me how our dear motherland is getting on” — that continued to sustain him post-independence, when the Nehruvian establishment and its hangers-on heaped calumny on him, marginalised and insulted him in their desperate attempt to drag and consign him to the dungeons of history. That Savarkar lived on despite them, that Savarkar lives on inspite of their best attempts to erase his contributions to India’s independence is a testimony to the man’s unique position in the pantheon of those who articulated Indian nationalism, battled for her emancipation and truly suffered and sacrificed themselves at the altar of that struggle without thought for recompense or recognition.

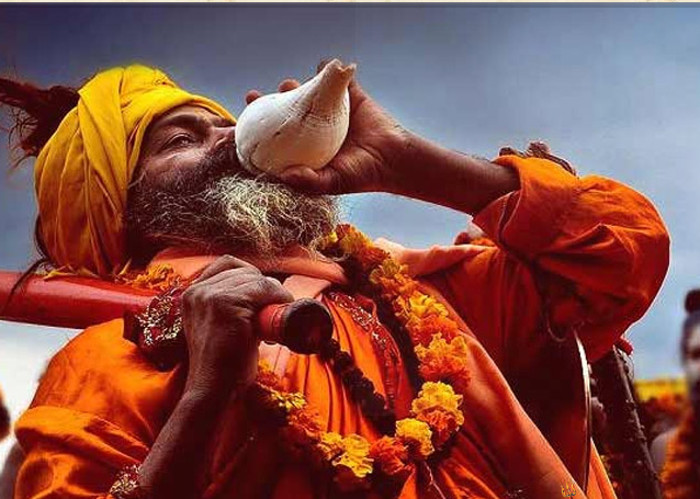

The Indian Oil Foundation, the Minister of State for Petroleum and Natural Gas Dharmendra Pradhan and BJP president Amit Shah who spent two days in the Andaman & Nicobar islands to re-ignite the Savarkar Jyoti — signifying the aspiration of freedom, symbolising the sacrifices made by thousands of countless patriots and hundreds of uncompromising revolutionaries who had their lives shattered and often smothered in the lonely and tortuous confines of the Cellular Jail — need to be lauded. The act of igniting the Savarkar flame has restored the dignity of the Cellular Jail and in it the memory of hundreds of revolutionaries who braved the most acute British atrocities and spent decades in the most sub-human confinement because they dared to “wage war against the King-Emperor” in their legitimate quest for India’s liberation and emancipation.

That dignity was desecrated in the past by a certain mindless Nehru and Gandhi family acolyte who in a fit of rage, displaying extreme intellectual barbarism and using the might of his official position as a Minister in the Government of India, brought down the plaque that commemorated Savarkar’s contribution and his incarceration in the Cellular Jail. That act of intellectual vandalism not only denigrated Savarkar but cast aspersions on the hundreds of revolutionaries who spent the best part of their youth holed up in the Kala Pani. More such flames thus need to be ignited across the country, more such commemorations need to be undertaken, more such unsung and undocumented heroes of our freedom struggle need to be discovered and feted and their lives and struggles serve to keep alight the flame of freedom in young minds. It is through the stories of these revolutionaries that one can really and essentially instil in young minds the reality of how freedom was indeed wrested at a great price.

I could not agree more with a young Russian Indologist I met during my recent visit to St Petersburg, who asked me why the stories of Indian revolutionaries have not been sufficiently told. I could not agree more with India enthusiasts in Berlin, who told me, while taking me around the museum dedicated to the victims of Nazi violence and Gestapo atrocities, on the need to have someday, a grand museum dedicated to the memory of Indian revolutionaries. That we do not yet have such a museum is indeed a reflection of the partisan approach that a section of our political establishment displayed towards this period of our history. One hardly talks of Barin Ghose, Upendra Nath Banerjee and Ullaskar Dutt who led the first batch of political prisoners connected to the Alipore Bomb case, who were deported to the Cellular Jail in 1909, spending a decade in the most trying conditions and yet not losing or diluting their ultimate goal of seeing the motherland free.

The Savarkar Jyoti thus shall not only keep ignited the flame of freedom, it should also re-kindle a genuine interest in this period of our struggle, an interest that may culminate in a grand memorial someday. As Shah rightly said, “The Savarkar Jyoti shall be a radiating source of inspiration and commemorate the countless revolutionaries who smilingly sacrificed themselves at the altar of freedom.”

That commemoration, in a sense, has now begun in right earnest, after nearly seven decades of passing through an imposed forgetfulness.

(The writer is director, Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation, New Delhi)